Dialogue caught up with Nayanika Mookherjee, a Professor in our Department of Anthropology who has been shortlisted for the PhD Supervisor of the Year award at the Postgrad Awards 2023.

Can you tell us a little bit about your work?

I am a Professor of Political Anthropology and one of the Co-Directors for the Institute of Advanced Study which seeks to promote interdisciplinary research. I look at how different political institutions, practices and phenomena are experienced by different communities, specialising in anthropology of violence and state. I have drawn on interdisciplinary perspectives to publish extensively on public memories of gendered violence during wars, debates on irreconciliation, violence, ethics, aesthetics and transnational adoption.

Based on my widely acclaimed book, I co-authored ethical guidelines, a graphic novel and an animation film through a historically and archivally informed, intergenerational family story and received the Praxis Award in 2019. Overall my research has been on the public memories of wartime sexual violence, memorialisation of wars, war crime tribunals, processes of reconciliation and irreconciliation, conflict and transnational adoption as well as digital surveillance, memorialisation of the history of the enslaved and the role of comics/graphic novels in translating difficult stories.

Nayanika Mookherjee after the film screening of Icecream Sellers (film shot in Rohingya camp) with Film Director Sohel Rahman, Phd students Tahura Enam Navile, Fiona McGrath and postdoctoral scholar Sadaf Noor Islam - all working with the Rohingya communities.

Congratulations on being shortlisted. What does this mean to you?

I am so very thankful and grateful for this opportunity. PhD students are the future of academia where cutting edge research lies and can enliven one’s own research, teaching, thinking and contribution to the wider world. Over the last few years, I have supervised 11 PhD students to timely completion (six with permanent positions, two with prestigious postdoctoral fellowships and publications). Currently I have 13 PhD students: four students who are near completion, one student who has returned from fieldwork, seven students who joined last year and one new student who will join this year.

I know this is a large number of PhD students, but it’s really interesting to see how their research projects overlap, intersect and enrich, which forms a cohort of research scholars where I am just the supervisor and merely connecting them up. Professionally it is supporting and growing the future cohort of scholars in the UK and beyond. Personally, PhD students are one’s research interlocuters and I learn so much from each of their projects and the interconnections between them. However, funding and employment on completion of their PhDs is a big issue, so I am trying to be proactive on those fronts. I think all of us in academia are lateral thinkers. I am keen to develop the interdisciplinary energies among my PhD cohort by always encouraging them to attend events which are not directly linked to their projects and help them develop lateral, sideways connections.

Why are you so passionate about Political Anthropology?

I am a feminist and a political anthropologist who is keen to highlight the perspectives of the ‘majority world’ (as coined by the Bangladeshi photographer and activist Shahidul Alam instead of global south) critically. All my areas of research on state, violence, gender, ethics, aesthetics, adoption are brought together by the need to ethnographically explore public memories of violent pasts and aesthetic practices of reparative futures. What this means is how do we engage with the various violent pasts that we live in today and how can these be resolved, how do we engage with the idea of justice through our zones of nurturance, through the law, the arts, through our senses so that we have a better future? I think these are big questions relevant for varied spheres and also brings academia into conversation with the wider world. Being passionate about your research is the cornerstone of being an academic and attempting to engage the debates in academia with that of the wider world is also crucial.

How did you get into Political Anthropology?

My research on the public memories of sexual violence during the Bangladesh war of 1971 was triggered by my outrage and despair as an undergraduate student in Kolkata/Calcutta, India, over the unfolding of inter-communal violence after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in India on 6 December 1992 by Hindu communalists. One of the main questions that troubled me as an undergraduate student in the early 1990s is why women were raped in the contexts of conflict. This was also the time when sexual violence in Bosnia and Rwanda were occurring. In these two events racialised differences and hierarchies were evident and it was clear that sexual violence during conflict is not treated similarly.

My research also drew inspiration from the rich scholarship on Partition violence in 1947 published in the 1990s by Veena Das, Urvashi Butalia, Ritu Menon. In recent years, having co-set up the BAME network at the University, conversations within the network started to critically explore how ‘diversity’ can become co-opted and how the role of law is important. My recent and ongoing projects engage with this role of the rule of law.

How does your research influence the way you teach Anthropology students?

My teaching is completely research led and it has allowed me to teach classical anthropological themes within contemporary debates for a long time. I love teaching the modules on political anthropology and particularly a third-year optional module titled ‘Violence and Memory’ which has had nearly 120 students. Since 2007, I have engaged with debates on memorialisation and forgettings in my module and the slavery walking tour fieldtrip in different cities across the UK. These guided tours have shown that in investigating these ‘absent presences’ of a city’s black history, it is important to move beyond the simplistic narratives of the region’s involvement in Abolitionism and to focus on the more complex nature of the extensive industrial ties to slave trade. Students considered these tours to be an exemplary template for good practice of decolonisation.

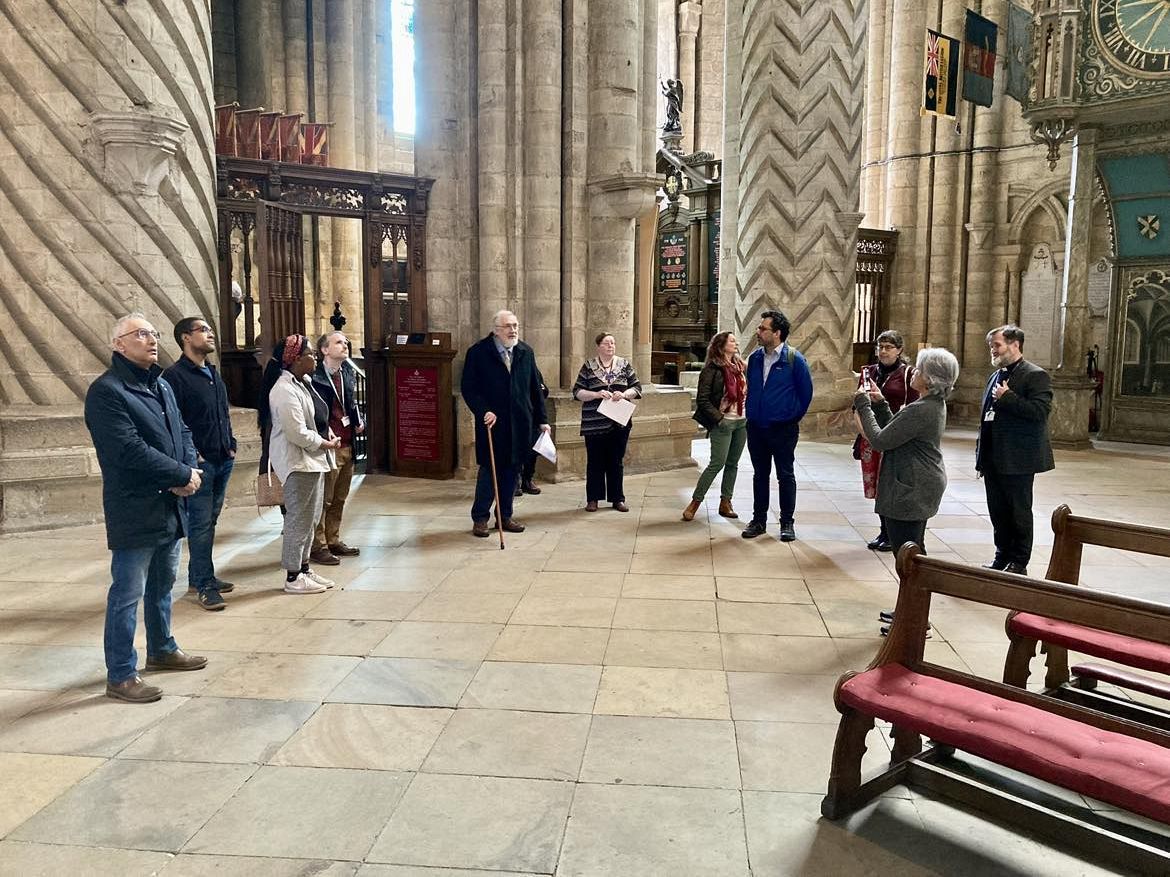

Nayanika Mookherjee carrying out the walking tour of the enslaved in Durham Cathedral as part of the IAS project (Absence presence of Durham’s Black history) with community historians, archivists, colleagues and Phd students, from the University including PVC EDI Dr Shaid Mahmood.

Tell us about a day in the life of a Professor in the Department of Anthropology.

My day starts very early. I try to do three hours of my own quiet writing work in the morning when there are no emails, meetings, and phone calls until 7.30am before the school run. My typical day can involve anything from teaching, meeting students, administrative writing work including PhD student script feedback, funding application support, writing references or doing some readings. I am also the Co-Director of the IAS and Chair of the Ethics Committee of the Department of Anthropology. Both are big administrative jobs but they are both research-facing jobs so I try and keep my afternoons free to respond to emails. I think finding the time for writing and reading during our cognitively overloaded days is key to finding the balance as an academic.