Ancient dung has helped provide our Archaeology researchers with the earliest evidence of animals being farmed for food.

Humans were tending animals approximately 12,500 years ago in Abu Hureyra, Syria, according to the research involving Emeritus Professor Peter Rowley-Conwy and led by the University of Connecticut, USA.

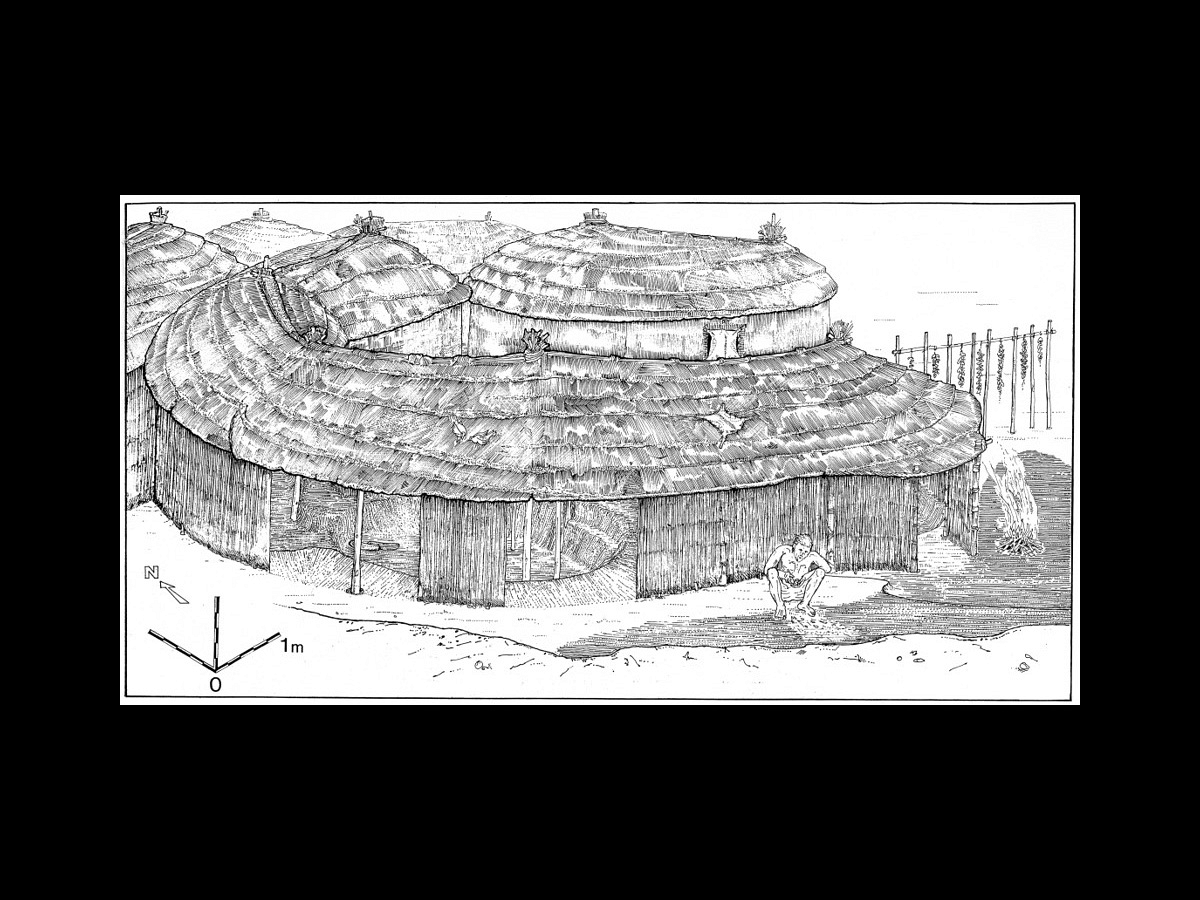

Neolithic house above Epipalaeolithic hut

Traditionally, archaeologists have looked for changes in the shapes of animal bone that vary between wild and domesticated animal populations as evidence of the move to tended animals.

While this provides a lot of information, changes to bone shape happened well after the process of tending and domestication began, leaving people's earliest experiments with animal management hard to track.

That’s where animal poo comes in.

Reconstruction of the hunter-gather hut dating to the Epipalaeolithic period. (Image credit: Andrew Moore).

Dung spherulites

Many herbivores form tiny calcium-based balls - called dung spherulites - in their intestines, which can be found in accumulations of dung produced where live animals are being kept.

Evidence of dung spherulites lets archaeologists examine the period before full domestication to see when people first began bringing live animals to sites to care for them.

Professor Alexia Smith, who took part in the research

Soil samples from Abu Hureyra contained an accumulation of spherulites found outside an ancient mud hut, which enabled the researchers to approximately date when the dung deposits were made.

As a result, they said that hunter-gatherers were bringing live animals, most likely sheep, to Abu Hureyra between 12,800 and 12,300 years ago to tend them.

They added that this was almost 2,000 years earlier than seen elsewhere, but was in line with what might be expected for the Euphrates Valley.

Professor Peter Rowley-Conwy, who took part in the research